Closer to Planet Nine?

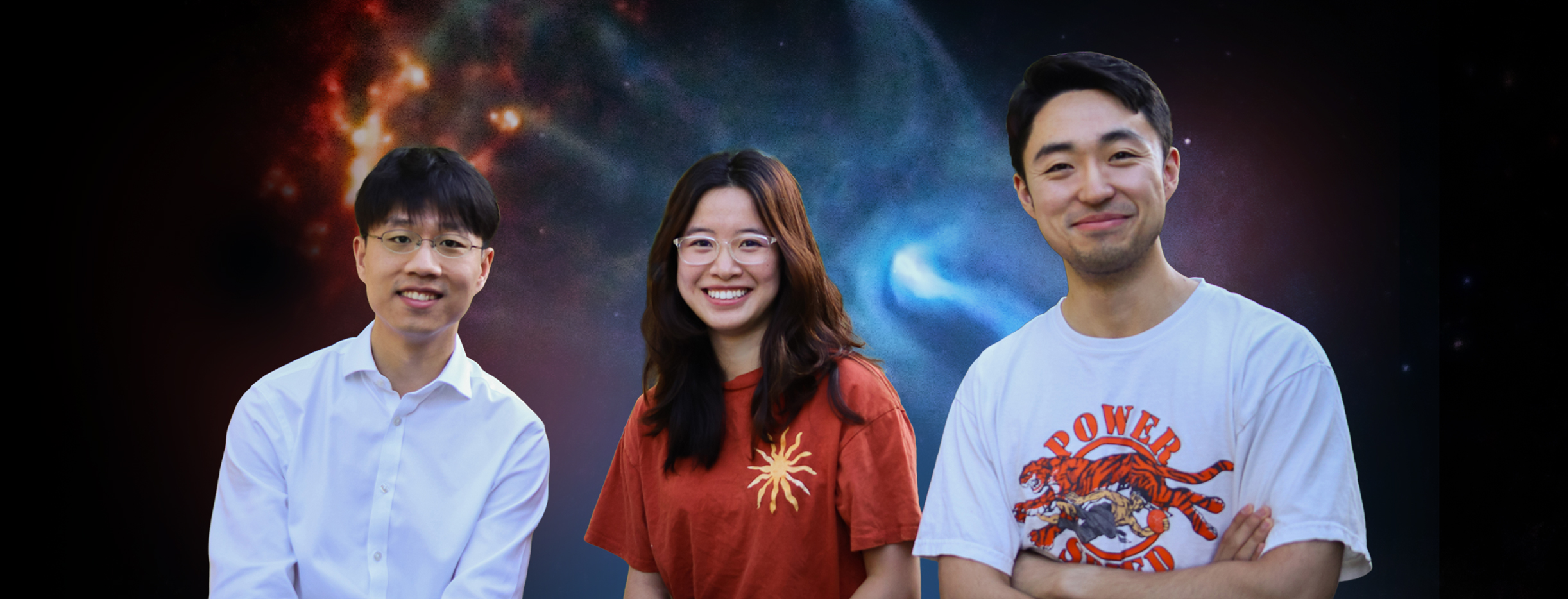

Recent graduate Eritas Yang and her colleagues at Princeton discover a dwarf planet, bringing new insights to the Planet Nine problem.

Eritas Yang ’24 has made a far-out discovery. After two colleagues spotted a new dwarf planet in our solar system, a key moment came when they asked Yang to contribute her physical intuition and numerical skills to their deep space investigation.

Yang majored in physics and was in the first year of her astrophysics PhD program at Princeton. Soon she noticed something strange about the dwarf’s orbit, a finding that could shake up scientists’ understanding of our planetary system.

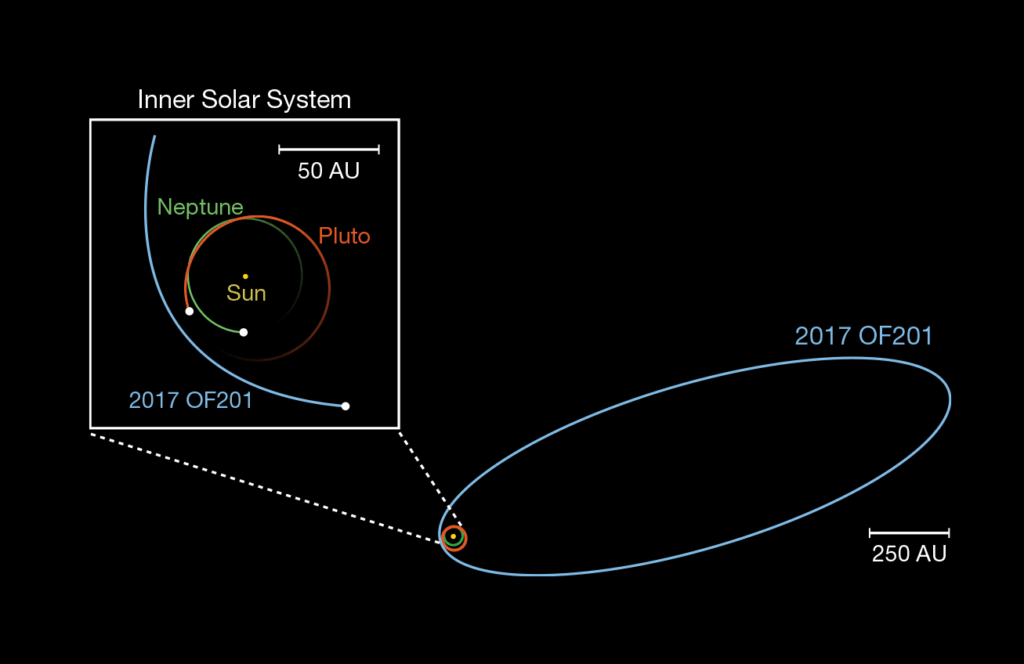

The temporary name of the celestial body is 2017 OF201, and it joins the group of extreme trans-Neptunian objects (eTNOs) due to its extremely wide orbit. Astronomers created the category of dwarf planets in 2006 for objects larger than asteroids that are too small to sweep their orbits clear of other bodies. With its estimated 435-mile diameter 2017 OF201 is substantially larger than other eTNOs and might be qualified as a dwarf planet, the same category as Pluto.

“From our observations, we realized that the orbit of 2017 OF201 is an outlier to the observed clustering of other TNOs, which has been interpreted as indirect evidence for the existence of a hypothetical Planet Nine,” says Yang. “Once we realized that, we got excited, because that meant we could bring new insights to the Planet Nine problem.”

Astronomers have speculated that this yet-to-be found far away ninth planet exists because orbits of other TNOs are in similar orientations they seem to be influenced by the gravity of an unknown larger object. But 2017 OF201’s orbit deviates from their pattern. Whether or not this serves as a counterargument to the Planet Nine hypothesis depends on the stability of this object. Yang is currently analyzing the long-term stability of its orbit with and without the presence of Planet Nine through numerical simulations.

When asked if she believes another planet lurks in the outer darkness, Yang says, “I’m neutral on this. I’m simply excited to see that this discovery has led to more studies and discussions of Planet Nine.”

Like other eTNOs, 2017 OF201 is fantastically remote. At its greatest distance, its elliptical orbit careens 157 billion miles from the Sun. Much of the difficulty in finding eTNO’s is that they spend almost all their time so far away they can’t be detected. Yang’s team got lucky spotting it because it was close enough to the Sun (8.3 billion miles) at the time of the discovery. Interestingly, it made its nearest approach of 4.1 billion miles in 1930, which coincidentally is when Pluto was discovered. The last time 2017 OF201 sped so near Earth was 24,256 years ago when hunter-gatherers are believed to have first reached North America. The fact that Yang’s team observed this one object opens the possibility that hundreds of other eTNOs remain unfound in the outer solar system; they are just too far away to be detectable.

Yang credits her knowledge of planetary dynamics to Harvey Mudd Assistant Professor of Physics Dan Tamayo. They wrote a paper on an analytical model for the long-term orbital dynamics of planetary systems. Thanks to her insights, Yang won the American Physical Society’s 2024 LeRoy Apker Award, the most prestigious honor that group bestows on an undergraduate.

“Eritas is a tenacious problem solver and thinker who won’t let go of a problem until she figures it out, and she’s also soft spoken and humble,” says Tamayo. “She blew all my expectations out the window and did an incredible job. It’s mind blowing that in her first year of grad school she’s involved in detecting something like this.”

“Amazing” is how Yang describes her experience with Tamayo. “He gave me lots of confidence in my ability to do future research.”

She says her path toward astrophysics was “super-random” and began with an interest in quantum mechanics while she was a high school student in Shanghai. “I felt it would be a real pity if I lived my whole life without knowing how the world functions in a scientific way,” she recalls.

At HMC, she loved to hike Mount Baldy, especially at night. She liked to persuade people to join her at 2 a.m. so they could see the sun rise from the summit. On one occasion she witnessed a meteor shower from the peak.

“It’s fun to hike in the dark,” she says. “You can feel yourself breathing. You feel the existence of yourself.”