Jacqueline Paver ’77 is helping women in the military make history.

In 2022, Paver—a biomechanical engineer focused on injury mechanics and prevention—signed an independent contract with the United States Air Force to do manikin development and testing for military warfare aircraft to safely accommodate small and pregnant women.

“Military aircraft have been evolving over the last couple of years,” she says. “Occupant compartments must be redesigned, and new aircrew personal protective equipment must be developed. Female aircrew must be able to reach and operate controls and have seats, helmets and suits that fit them.” Helmets that are too heavy can cause neck injury, and poor positioning can lead to fatigue. Examining ejection systems is one of Paver’s recent projects. Ejection seats designed for males, she explains, have catapults that are extremely aggressive, which can lead to lumbar spine compression fractures. She’s looking at a programmable catapult that would accommodate petite and pregnant females.

In January 2023, Major Lauren Olme of the 77th Weapons Squadron became one of the first pregnant air crew members to fly an ejection seat aircraft—a B1 Lancer supersonic bomber—thanks to a policy that authorizes pregnant aircrew to apply for a waiver “regardless of trimester, aircraft or flight profile,” according to an April 11, 2022 Air Force Public Affairs news article. “Waivers are important, but programmable ejection seat catapults and modified restraints will reduce the likelihood and severity of fetal injury,” Paver says. “My hypothesis is that we can redesign the ejection seat in the cockpit essentially using technologies that have been developed from automotive pregnant injury research.”

The Center for Injury Research, where Paver is president, contains an extensive physical and virtual library of journals, books, conference proceedings, papers, reports and videos of crash tests, and models of product liability defects.

Automotive injury research is Paver’s bread and butter as a longtime independent consultant and as the president of the Center for Injury Research in Santa Barbara. The center’s mission is to mitigate injury and prevent death through scientific research on crashworthiness, biomechanical engineering and occupant safety.

Paver’s path to biomechanical engineering and injury research began 50 years ago at Harvey Mudd. She studied engineering almost by process of elimination after finding that neither chemistry nor physics nor mathematics suited her fancy.

Once ensconced in the engineering department, the classes that most piqued her interest were in failure mechanics; it was her introduction to injury mechanisms. “If you twist a bone, you get a spiral fracture. If you bend a bone, you get a transverse fracture. If you compress a bone, you get a different fracture pattern,” she says. “My question was: Can you look at the fracture pattern, work backward and figure out how the forces are applied? And then can you look at how the forces were applied and relate it to the fracture patterns?”

“I got into failure and how the body breaks, understanding the body and how to protect it by creating anthropomorphic models.”

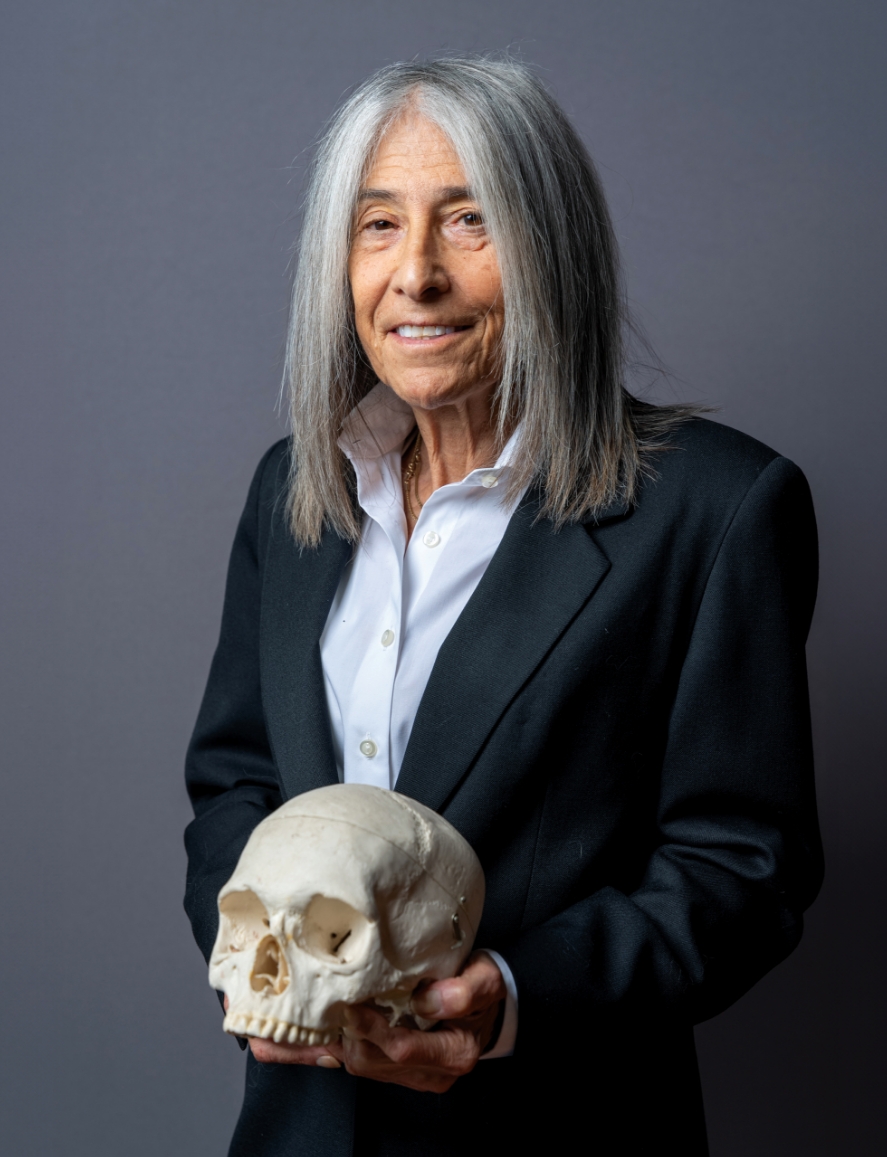

Jacqueline Paver ’77

Paver also credits her Engineering Clinic project for having a profound effect. “Something I learned at Harvey Mudd was how to solve problems,” she says. “That’s worth so much more than expertise in a particular field.”

After graduation, Paver went on to graduate school at Duke University, one of the few schools offering a master’s degree in biomedical engineering at the time. “My focus was head and spine injury and protection, simulation modeling and testing. I tested helmets. I tested spines. I tested cadaver responses to see how they failed. Then I made simulations of them and got into dummy development.”

She earned her PhD in biomechanical engineering, spending summers at the Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio, where she worked on head and spinal injury simulations in the manikin lab. At the time, biomedical engineering was a new field. “I got into failure and how the body breaks,” says Paver, “understanding the body and how to protect it by creating anthropomorphic models.”

She also began giving expert testimony in litigation cases, focusing on how a vehicle, or perhaps a helmet, had failed, which led to trying to understand and envision what alternate designs might be available. She also researched injuries from slips, trips and falls, including from heights, and from diving into shallow water. “You’d be surprised how many people don’t take responsibility for their actions, number one,” she says. “Number two, you’d be surprised how many people dive into shallow water or dive into water of unknown depth.”

The Center for Injury Research team was integral in upgrading Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standard 216, a laboratory test procedure for roof crush resistance, taking it from a quasi-static rollover test to a dynamic rollover test, which uses dummies to measure injury potential.

In the 1980s, she met Donald Friedman, a pioneer of vehicle crashworthiness and occupant safety research and testing. The two kept in touch. In 2001, Friedman founded the Center for Injury Research and, several years later, she traveled to Santa Barbara for a seminar on litigation criteria for evidence. In 2010, Paver joined its board of directors. In 2016, a year after Friedman’s death, she became president.

Paver and the Center for Injury Research (CfIR) team examine airbag and restraint defect injuries (like seat-activated airbag deployment, seatbelts and latching). CfIR was also integral in upgrading Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standard 216, a laboratory test procedure for roof crush resistance, taking it from a quasi-static rollover test—containing no occupants and no injury measures—to a dynamic rollover test, which uses dummies to measure injury potential. Such tests and standards are regulated by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, whom the CfIR also petitioned regarding defects in seat-activated airbag deployment.

“Say a mother was sitting in the passenger seat, reached into the back seat to adjust their child’s seat belt, lifting their buttocks from the seat,” Paver explains. “If they got in a crash, the driver airbag would deploy, but the passenger airbag would not.” CfIR also maintains a huge online and physical library related to crashworthiness and biomechanical engineering.

Though contracted as a sole proprietor, Paver is working hand-in-glove with her colleagues at the CfIR on the Air Force research, which will help create safe opportunities for all women—pregnant or not—to advance in their military careers. This is important to Paver.

While in recent years Harvey Mudd has earned renown for providing STEM opportunities for women, when Paver arrived on campus in 1973, female students weren’t abundant; she was one of about 50 women in the student body. “It’s incredible to see where Mudd is now compared to where it was when I started,” Paver says. “I think women were well-respected at Harvey Mudd when I was there, but we were an anomaly.” At the time, women were required to live at Scripps College. She took on the role of women’s proctor in her junior year, acting as a mentor for her fellow female students.

Her enthusiasm and passion to pay it forward hasn’t waned; Paver relishes any opportunity to share her unique area of expertise, developed over half a century, and mentor women who want to pursue a career in biomechanical engineering.