Summer in the City of Photochemistry

Researchers study photochemistry in Paris.

Ahh, summertime in Paris—known for late sunsets and warm weather, walks along the Seine and leisurely meals at sidewalk cafés. This season in the City of Light is also known—to atmospheric chemists, at least—for something else: very active photochemistry. That’s what brought Lelia Hawkins, Hixon Center director and Hixon Professor of Climate Studies, and two of her students to France for research in June 2022.

Hawkins, Drew Pronovost ’23 and Sydney Riley ’24 participated in the ACROSS campaign, a large field study designed to examine, with as much detail as possible, how an urban plume of pollution might influence the chemistry of the forest air and vice versa.

“The components of each system interact with each other, and the chemistry is non-linear and not well modeled,” says Hawkins. “This is important because many forested sites are close enough to cities to have some influence of the pollution from cities in the forest, and because heavily forested areas also emit compounds to the atmosphere that can play a role in making hazardous compounds, like ozone, when other human-generated pollutants are present, like nitrogen oxides.”

The field study, which included researchers from France, the U.S. and other nations, took place over three sites: a city site in Paris, a forest site in Rambouillet (about 25 miles southwest of Paris) and an aerial site, for which instruments were mounted to an airplane that flew above the city center. “In the city site, we had six different filter samplers, cloud radar and about 15 instruments inside a small structure, with a hole and tubing to sample through. We had gas phase analyzers (ozone and nitrogen oxides), we had a few mass spectrometers to look in chemical detail, and we had ways to count and size the particles, too,” Hawkins says.

Most days, Pronovost and Riley walked to work from their apartment on the right bank of the Seine to the field site across the river. “We got a shot of espresso and a fresh pastry for breakfast on the way,” says Riley. “We also used the metro system extensively, including for evening commutes to complete sunset filter changes. The instruments at the city site were run out of a classroom on the eighth floor of a University of Paris building, with roof access.”

Having multiple sites managed by multiple research groups is what makes this study one of the larger efforts to measure the complexity of the atmosphere. “The impact is large, too,” Hawkins says, “because you can start to answer questions you couldn’t answer before since you have a more complete picture of the chemistry. Depending on what is found, laboratory studies can be designed to focus on the potential for certain emissions (like organics from trees) to form secondary pollutants, like aerosol material.”

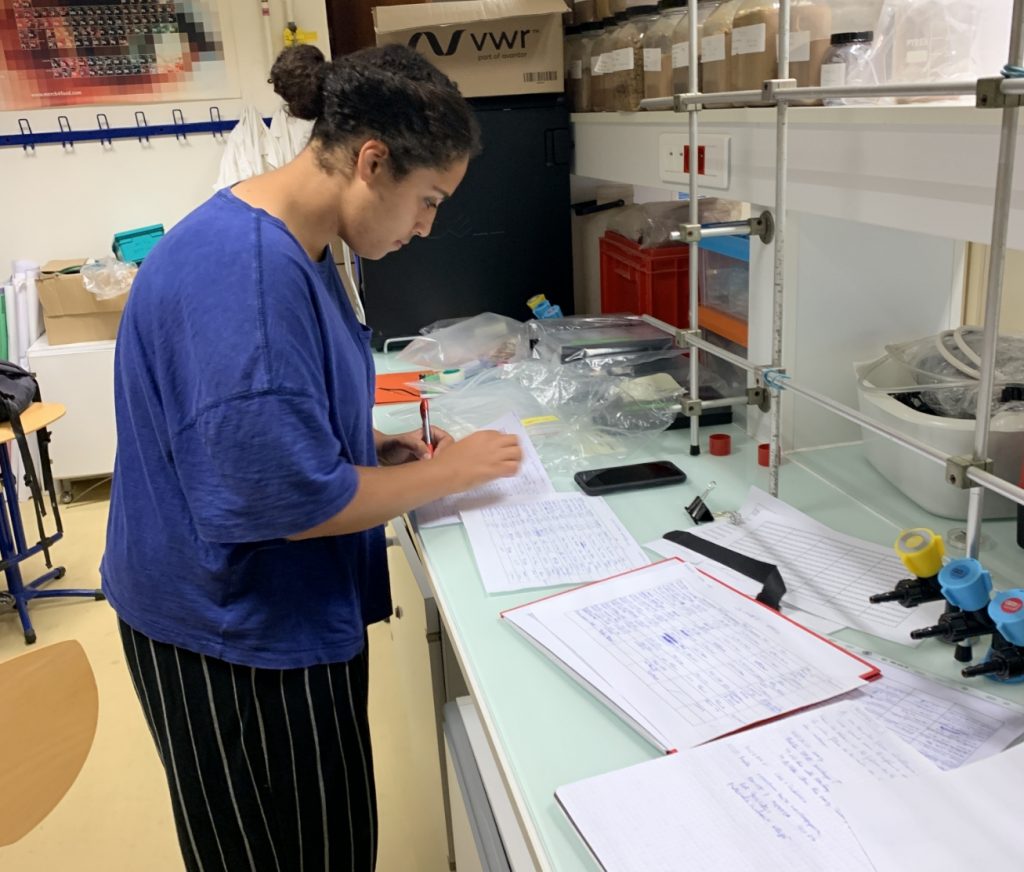

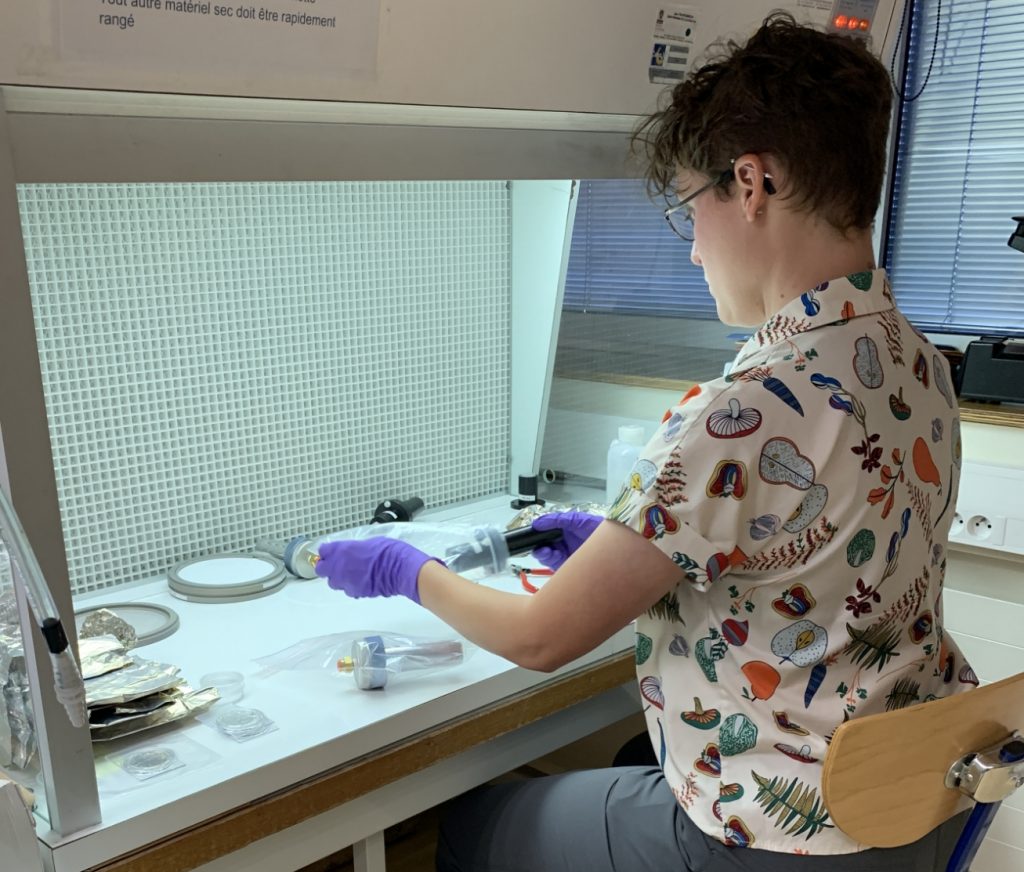

Pronovost (a chemistry major) and Riley (engineering), two of just a few undergraduates among the researchers, focused on data collection at the city site. “There was a lot of trust placed in us in terms of collecting data and working with instrumentation on our own,” says Riley. “It was my first time working with research-grade instrumentation outside of a supervised academic lab course. Once I was trained, my daily responsibility was to collect and plot the data, then post it so other scientists on the campaign could see it. It was all preliminary data, but I felt that what I was working on was a real contribution to the campaign and useful for the other scientists to glance at and get a rough idea of the trends in gas phase compounds from day to day.”

Both students found the challenges of fieldwork surprising. “I knew it would be an intense experience,” Pronovost says, “but I still wasn’t entirely prepared for the true intensity of dealing with a suddenly overheating instrument or a part shortage. Work was very improvisational and collaborative. I had to constantly work with people I didn’t know well from all over the world, and we had to navigate everything from frustrating time zone differences to power outages.”

“More than anything, it was important to be ready to jump in and help when a problem popped up,” says Riley. “Fieldwork involved a considerable amount of flexibility, and it was nice to be solving problems in a real work environment after trying to practice those skills at Mudd.”

Hawkins concurs. “The data processing can be tedious, and there is manual labor like filter changes (twice a day, every day), and if you miss an hour or a half a day of data, you can’t get it back.”

But it’s worth it. “The most enjoyable part was getting to direct my research,” Pronovost says. “My dream is to lead my research and teach as a professor, and this experience gave me a taste of independent research and what it’s like to be in a field campaign.”

“Being a part of the ACROSS campaign was really special because there were scientists from all over the world working together,” says Riley. “It opened my eyes to the complexity and importance of atmospheric chemistry and its implications. Talking to experienced scientists from different places, focused on all different kinds of atmospheric research, who came together to collaborate and help each other get the measurements for the campaign was exciting. There was so much to learn from all the people around me, and they were all ready to explain and discuss. Just listening in on conversations between other scientists, I feel like I learned and understood the science and its importance more deeply than you can in a classroom setting. It was exciting to see the chemical reactions I learned about in theory actually correlate to the changes in gas concentrations that the instrument was capturing.”

Hawkins enjoyed working with scientists from France “to do something bigger than any of us could do alone and to do atmospheric chemistry with Drew and Sydney, so they could see what it really feels like to do this work. It’s hard to explain to someone how challenging and also how fun it can be to collect high-quality data. You have to be creative, attentive and cooperative. I love this kind of work. I also love seeing how quickly the students learn.”