Faculty

Trajectories

Creative writing Professor Salvador Plascencia wants to see where the imagination can go.

FOR SALVADOR PLASCENCIA, WRITING IS NOT A science, but a logistical problem.

“How do you move this character there?” the College’s new assistant professor of creative writing reflects. “How do you get this character to fight that character? How do you heal that character, get him to the hospital? It’s logistics.”

For a writer often labeled as experimental, Plascencia is surprisingly interested in writing’s moving parts: words, syntax, the labor-intensive stuff of grammar. Close reading. Sentence isolation. While his literature courses explore broad problems related to politics, history and identity, in his workshops, the sentence is king. He’s fond of employing constraint exercises—short spurts of prose that focus on those diminutive yet crucial mechanics. A lipogram, for example, might require students to pen 300 words without using the letter “e.” Or students might “inherit” a century-old word bank and construct something syntactically new from this list.

Plascencia

“Anytime there’s intense focus on the word or the sentence, that’s really what we want to do,” he says. “Pragmatically, we can’t all write novels and talk about them in a workshop setting. I’m much more interested in the sustained effort of a single page.”

Following creative writing positions at Pitzer and Pomona colleges, as well as at UC Riverside, USC and CalArts, Plascencia heard about an opening at Harvey Mudd through the 5-C grapevine. He says he wasn’t daunted by the idea of teaching writing at a STEM institution. Plascencia’s interest is in magical realism, a genre that incorporates fantastical or mythical elements into an otherwise realistic narrative.

“So that’s probably not science related,” he says jokingly. “My critical inquiry class is called Unreality, so we’ll be looking at [Gabriel García] Márquez, [Jorge Luis] Borges. I have not really thought about any sort of technically related thing.”

He does not envision STEM shaping his instruction in major ways, at least to start.

“My function is to explore humanities,” says Plascencia. He aims to teach writing as craft, rather than explore broad, conscious themes related to science or otherwise. He’s also not concerned with students (or himself) getting published.

“I think about whether a piece of writing has potential trajectories that are exciting to me,” he says. “My hope is students never try to tame or correct what’s happening, but rather be open to the potential of what it could be.”

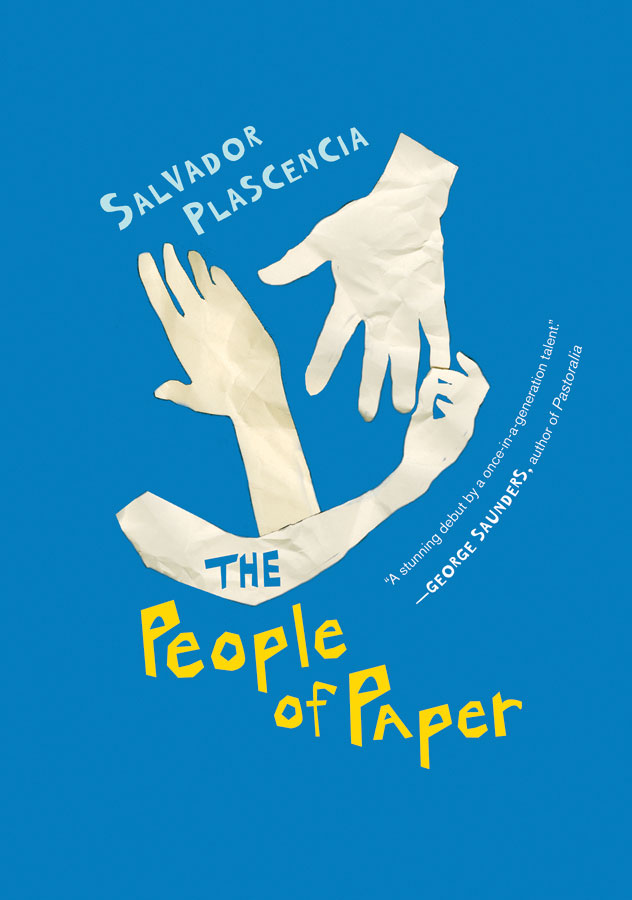

Plascencia’s own novel, The People of Paper (McSweeney’s Books, 2005), was rejected by more than a few major publishers. “All of them,” he says rather proudly. (Many of these same publishers scrambled after the fact to release the paperback.)

Now translated into a dozen languages, The People of Paper has received critical acclaim and earned him the Bard College Fiction Prize/writing residency in 2008. His stories and reviews have appeared in Los Angeles Times, Tin House and McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern. Poets & Writers called Plascencia one of the 50 most inspiring living authors in the world, noting “Plascencia alters our experience of the text and challenges our associations of symbol and meaning by incorporating drawings, figures and text objects into his writing.”

Still, he remains reluctant to qualify writing in terms of accolades or publishing credits.

“My first draft [of The People of Paper] was a B- story in an undergraduate workshop,” he says. “But the way we talked about it was not ‘how to fix it,’ but ‘where can this go?’ So I’m far more interested in the trajectories of where the imagination can go than in controlling or taming it.”

After graduating from Whittier College with a B.A., Plascencia went on to Syracuse for an MFA in creative writing, studying under author George Saunders, whom he considers a mentor.

Now in the instructor’s seat himself, he’s taught numerous creative writing workshops and a slew of interesting literature classes, including fall semester’s Lit 179L: The Novel as a Print Technology. He’s at work on various writing projects—most notably a novel about a newly discovered ocean in Southern California’s San Gabriel Valley, which he admits he’s “having trouble finishing.”

For now he relishes the chance to introduce his favorite works—books by James Baldwin, Roberto Bolaño, Borges, Márquez—to a new crop of “sophisticated readers” who “are able to take the text and talk about it in any way.” Acclimating to the Harvey Mudd environment is also a priority, he says, and the cross-disciplinary nature of the College intrigues him.

“Ken [Fandell] is next door, a photographer, and then Gary [Evans], an economist, and this idea that it’s all close together—conversations with people in different areas of expertise are basically built into the architecture of the campus. In other places, all I had [nearby] were other English professors. So even just how you bounce around campus, it makes these conversations possible.”