Airplane Mode

An ambitious project by engineering professor David Harris and his HMC Aero Lab students takes flight.

In March 2017, engineering professor David Harris assembled a team of students in the Harvey Mudd College Aero Lab for an exciting project: the construction of an airplane. Over the next three years, more than 50 Mudders, 13 high school students and several mentors would squeeze thousands of rivets and spend a collective 6,100 hours to complete the Vans RV-7A.

“The purpose of this project was to give students hands-on experience with aviation, manufacturing, instrumentation and problem-solving by building a kit airplane,” says Harris, Harvey S. Mudd Professor of Engineering Design. “It was an opportunity for small groups of students to work alongside a faculty member on a nontrivial project.”

“I never thought I’d work on an airplane in college, but I certainly didn’t turn it down when I saw the email to work on it,” says Laura Gordon ’21, whose decision to become an engineering major was reinforced by the project. Here, she is making the “big cut,” separating the canopy from the windshield.

Harris and his Aero Lab team set up shop in the Parsons Engineering Building basement, and from mid-2017 through the fall of 2018, they built the airplane’s tail section (empennage). Supported by the Jay Wolkin ’99 and Clay Family Foundation Fellowship as well as alumni donations, Reem Alkhamis ’21, Roger Hooper ’19, Jonathan Schallert ’20 and Curtis Shinn ’19 spent summer 2018 working full-time on the airplane, with help from part-time volunteer high school students, to complete the wings and fuselage.

“I am always looking for opportunities to learn more and gain more experience in aerospace, so I was naturally drawn to Professor Harris’ airplane project,” Hooper says. “How could I pass up the opportunity to take part in building an airplane with my own hands?”

Not only was the work exciting and motivational for those involved in the project, but it also became something of an attraction on campus. Members of the faculty and staff brought their children to the Parsons basement hallway, where, through the lab’s floor-to-ceiling windows, they could watch the students shape and drill the raw aluminum stock into recognizable pieces of the plane. After a few weeks, the Office of Admission and Financial Aid began including the lab on tours of the campus.

“The plane was a great attraction,” says Thyra Briggs, vice president for Admission and Financial Aid. “The summer the plane first appeared on our tours, we certainly heard a lot about it, and this carried into the fall as we were visiting high schools around the country. Visitors loved to see not only the scope of what students were working on but also that they were working alongside a faculty member. Visitors and applicants always comment on the accessibility of our faculty, and the plane project was another example of that.”

“The most rewarding part of the project was getting to see the entire plane come together. There was enough there to make it look like an actual plane was sitting in that room, and it made me feel really good knowing that my hands took part in building it.” ROGER HOOPER ’19

That fall, the Aero Lab team test-mounted the wings and empennage to the fuselage. After that, they began to install the various systems (electrical, plumbing), selected the avionics and interior, and designed custom sensors and an augmented reality system. “The most rewarding part of the project was getting to see the entire plane come together,” Hooper says. “There was enough there to make it look like an actual plane was sitting in that room, and it made me feel really good knowing that my hands took part in building it.”

Harris says, “The best part is seeing the students grow in their confidence. These students are already very strong, so they started off well, but after working on the project for several weeks, they became true craftspeople.”

Ground crew

The broad scope of the project meant that it was accessible to a variety of students, regardless of their previous coursework or expertise. Those with more experience and knowledge were able to focus on trickier elements, like the fuel tanks, which have to be simultaneously assembled and sealed. First-year students and high school students with no specialized coursework had the opportunity to learn skills and then put them to use on tasks like riveting and wiring.

Several aspects of the build required specialized tools, which the Aero Lab team fabricated with the help of HMC machine shop managers Drew Price and his predecessor, Paul Stovall. “Most of the time I spent involved with the project was bringing over different assortments of special tools or making custom fittings or fixtures to make it easier to put something together or to make adjustments,” Price says. “There were lots of requests for a custom tool to make some particular task a little easier, and I loved coordinating with the team to identify those problems.”

Price notes that, at every step of the process, students gained practical skills in the shop as well as learning teamwork and problem solving. “Everyone who worked on the project had a special set of talents and interests,” he says, “and everyone had to learn new things along the way. Airplanes are complicated, but they are contained and are a wonderful analog for continuous learning to achieve a high-performing result.”

During spring break in 2019, Harris, Alkhamis, Schallert and Max Tepermeister ’20 traveled to Texas to build the plane’s engine at Superior Aircraft under the supervision of factory mechanic Darrell Ingle. The students placed the crankshaft and rods on a stand. They coated the two halves of the case with an adhesive. A silk thread was laid between the halves to fill any tiny gaps remaining before the case was bolted together. They assembled the cylinders and accessories. “We finished in time to watch the first engine test run, with a blast of flame coming out the exhaust,” Harris says.

That summer, Joseph Anderson ’21, Laura Gordon ’21, Sabrina Shen ’21, Yuki Wang ’22 and four high school student volunteers completed the sliding canopy, firewall-forward (engine and cowling) and avionics.

Instructor of Aeronautics Emerita Iris Critchell speaks with students about the College’s long history of integrating aviation and education.

One of Gordon’s tasks was to trim the expensive and fragile plexiglass canopy bubble, then cut it into separate parts to form the sliding canopy and windshield. “The first challenge was not cracking the plexiglass, since this would have required buying an entire new bubble,” Gordon says. “I practiced cutting the plexi several times, even breaking a cutting tool due to overheating. Once it had been cut to size for the canopy and windshield overall, the biggest challenge was the ’big cut,’ cutting to separate what would be the canopy from the windshield. After taking pains to ensure that it was in the correct position, the cut was made, despite my terror. Gluing it was another trial, but it felt great that it was complete and I wouldn’t have to worry about it breaking. Also, I was proud that this important part was done without major error.”

Shen says she found building the canopy to be an especially impactful experience. “The canopy itself was fairly geometrically complex and allowed me to build a lot of mechanical intuition while working on it since I had to shape all of the metal components by hand, often with the help of multiple clamps and ratchet straps,” she says.

An added challenge arose when the team decided to change the method of attaching the canopy from machine screws, as instructed by the schematic, to using Sikaflex, a polyurethane sealant. “Because of this change,” Shen says, “I had to make adjustments to a lot of the components as well as create completely new assembly instructions. With the added pressure of working with components that amounted to thousands of dollars, I definitely felt a great sense of responsibility for the work I was doing, and I am very satisfied with how it turned out.”

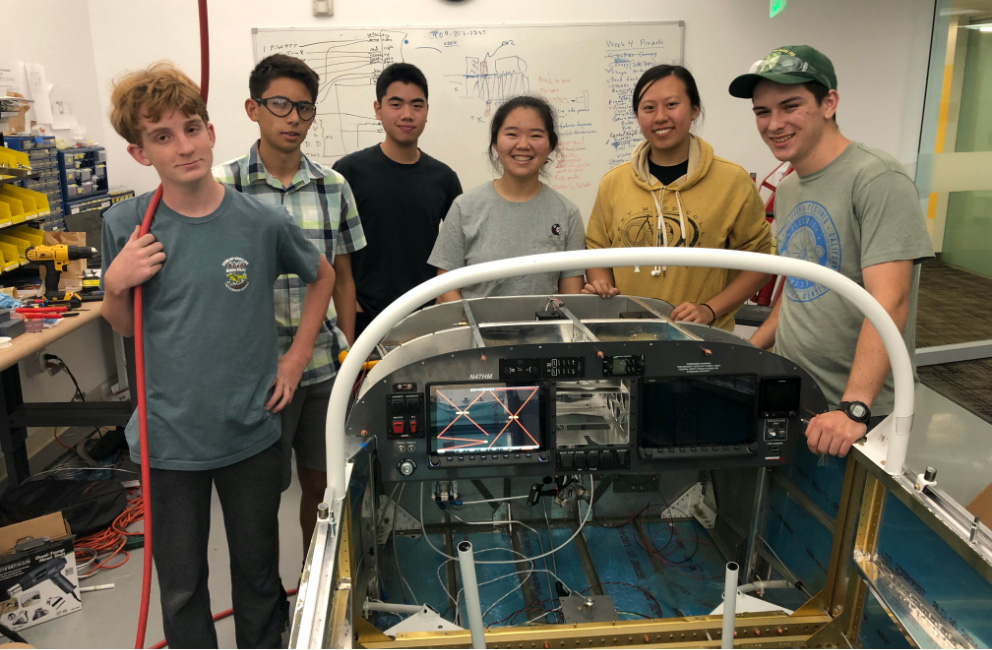

In Summer 2019, grade school students Abraham Harris, Jaden Clark and Matthew Chen and Yuki Wang ’22, Sabrina Shen ’21 and Joseph Anderson ’21 powered up the panel for the first time.

Wang mounted and wired avionics and did fiberglass work on the fairings, and Anderson drilled the firewall and began mounting systems and assembled the wheels and landing gear. Five weeks into summer 2019, the plane was ready to be assembled, so the team transferred the operation to a much larger space in a hangar at Cable Airport.

Ready for takeoff

From their new workspace at Cable, which had a view of aircraft taking off and landing, the team set the fuselage on the landing gear and mounted the engine. They mounted the sliding canopy and built the skirts, installed the instrument panel, ran the avionics wiring and antennas, plumbed the engine and built the baffles and cowling.

By the end of the fall 2019 semester, the plane was almost complete. “Seeing the engine running for the first time definitely brought me an overwhelming sense of accomplishment,” says Shen. “My teammates and I had put a lot of work into the build, often driving to the hangar whenever we had free time or even staying and working past midnight just to try and make a little extra progress.”

Spring 2020 brought new hurdles, namely, campus closure due to the pandemic, but the team worked diligently and, in early March, the plane received its final inspection and was issued an experimental airworthiness certificate. “When we heard that Harvey Mudd was transitioning to remote learning in the spring, we all knew that we wanted to see the plane running before we had to leave,” Shen says. “During those last three days, the team and Prof. Harris worked non-stop to the very last moment (one of our teammates started his journey home directly from the hangar) in order to get the plane to a semi-complete state. I think that during that period of chaos and anxiety as the effects of the pandemic reached campus, this was one of the few highlights.”

On the Horizon

After purchasing the plane, Harris began thinking about the next AeroLab build: an RV12iS light sport aircraft. “The directions are far more complete and include the engine and avionics, so all the phases of construction will be more accessible than the RV-7A was to beginning students,” Harris says. “It comes with holes predrilled to final size and is mostly assembled with pop rivets, saving hundreds of hours of match drilling and dimpling.”

After purchasing the plane from the College, Harris had it painted and detailed. He’s already thinking about the next AeroLab build.

Students who helped build the RV-7A are unanimous in recommending the experience to other Mudders. “I think that the Aero Lab is a fantastic opportunity for anyone interested in getting some real hands-on experiences,” says Shen. “Prof. Harris is super welcoming and supportive of anyone who wants to take part and is always eager to take in and mentor underclassmen. Even if someone is not looking to work in specifically mechanical engineering or aerospace related fields, I still think that it is a great experience to build professional problem-solving and communication skills as well as simply a good chance to be a part of a fun and fulfilling project.”

Project Propellors

In addition to learning from HMC faculty and staff and from each other, students received mentorship from an impressive group of engineering and aviation experts. Alex Mouschovias, a Clinic liaison, expert mechanical engineer and commercial pilot, assisted the team regularly. Tim Cook, a retired Boeing chief engineer with experience on the Space Shuttle, satellite systems and classified projects, taught the team fiberglass technique, painting, the finer points of sheet metal construction and fasteners and also gave students career mentorship.

Fred LaForge, the EAA technical counselor at Cable Airport, guided the team through firewall-forward steps. Along with several other experimental aircraft builders at Cable Airport, “LaForge visited our hangar nearly daily in July and taught us many things,” Harris says. “We have had terrific tours of many unique aircraft at Cable, including home-builts and warbirds.”

Instructor of Aeronautics Emerita Iris Critchell, who turned 100 in December, spoke with the students about Harvey Mudd College’s long history of integrating aviation and education. Barbara Filkins ’75 (physics) organized two fly-ins at Cable, sharing a Twin Velocity that she and her husband, Dale, had built.