Space to Grieve

In the health care field, physicians, nurses and caregivers often feel pressure, either from others or from within, to block out any emotions or attachments they may feel toward the patients in their care.

Senior Kaitlyn Paulsen, who is double majoring in human-centered design and engineering, and project partner Anya Zimmerman-Smith CMC ’21, whose work on this project was part of her thesis in humancentered design, wanted to help caregivers find a way to deal with difficult emotions. As part of an independent study project titled “Caring for Caregivers: Spreading Collaborative Grief Support Using Human-Centered Design,” the duo researched the stereotypes and realities surrounding emotions within the health care profession. They learned that having a space to express and process those emotions, particularly grief, helps prevent burnout among health care providers, a condition that costs the United States $4.6 billion a year.

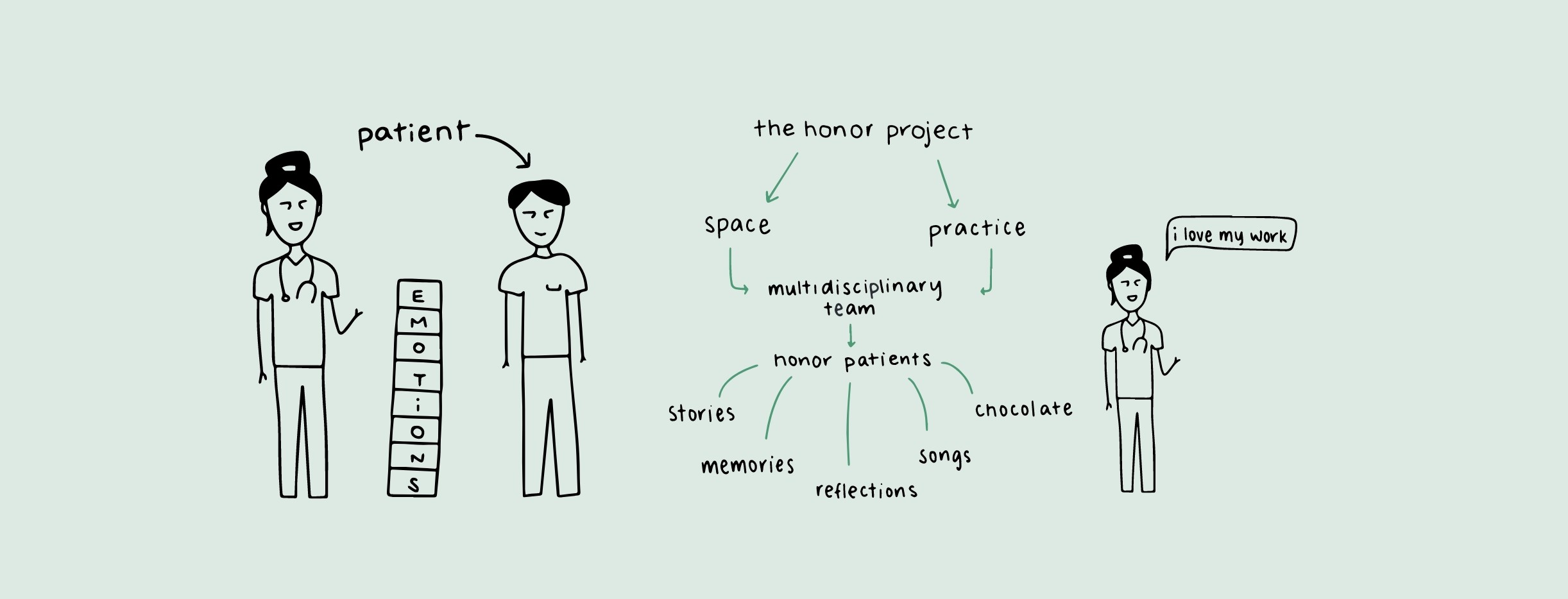

During their research, they discovered The Honor Project, a practice already being used at the University of California San Francisco Medical Center to benefit neuro-oncologists and their medical teams. Because brain cancer is often fatal, neuro-oncologists frequently encounter grief—including their own.

“The Honor Project created an intentional space within the workday where doctors, nurses, social workers and researchers can gather to share and reflect on their emotions,” Paulsen says. “This practice acknowledges the humanity of health care professionals and challenges the stereotype of needing to stay emotionally detached.”

“Through all our research, we saw that the effect of loss and grief on health care professionals is profound and complex,” Zimmerman-Smith says. “So we wanted to define what The Honor Project does in hopes of showing people that it solves these needs that we found to exist.”

The Honor Project was the brainchild of Rosemary Rossi, a social worker at the UCSF Brain Tumor Center, and Dr. Susan Chang, director of the division of UCSF Neuro-Oncology and the medical director for the Gordon Murray Caregiver Program and Sheri Sobrato Brisson Survivorship programs. After learning about the practice, Paulsen and Zimmerman-Smith set out to develop a way to share The Honor Project with medical communities throughout the nation.

To persuade hospital administrators that The Honor Project is needed in the medical field, Paulsen and Zimmerman-Smith found a way to describe how the practice helps health care providers cope with their grief. They produced a three-minute, hand-illustrated video that aims not only to explain the project, but also to address potential reluctance to adopting the practice.

“The video was a place where all these insights could be gathered in a much more succinct and personable way,” Paulsen says.

Feedback from many sources helped direct the video’s development. The two students also created an implementation guide to help administrators get started.

“They did some really great and difficult research into the emotions and impact that terminal illness and likely death have on caregivers and medical staff,” says the students’ project adviser Fred Leichter, HMC clinical professor of engineering and executive director of the Rick and Susan Sontag Center for Collaborative Creativity. “Their video and material were so well received that Dr. Susan Chang sent the material to her counterparts, the heads of neuro-oncology at every major research hospital in the country.”

Organizations such as MD Anderson, Mayo Clinic and the National Institutes of Health have already shown interest in adopting the practice.

Chang, as a co-designer of the project, discovered that The Honor Project she had helped create at UCSF was a human-centered design practice, even though the formal concept of human-centered design was new to her.

“I never thought of it as a formulated way of approaching the design of a program that never existed before, so this is very eye-opening to me,” Chang says. “Anya and Kaitlyn are so eloquent and compassionate, and it was a joy to partner with them. Because I see The Honor Project as very important and valuable, I hope through their work we can extend this to our global neuro-oncology community of health care providers.”

Human-centered design isn’t a major at Harvey Mudd. Paulsen took a single humancentered design class and was hooked. After she had taken the three human-centered design courses offered, she developed a proposal to create her own major. Her proposal included courses in engineering, psychology, anthropology, art and design, reasoning that human-centered design is an “interdisciplinary field that bridges technical product design and mechanical design skills with its emotional, sociocultural, environmental, visual and anthropological context.”

Paulsen stresses empathy as a necessary factor in successful human-centered design projects. She says her extensive interviews with health care providers helped her understand how they cope with emotion— whether they build walls to block out feelings or struggle with their grief alone. She also learned that some doctors and administrators might be reluctant to adopt a practice that would take time and resources away from their primary job. The video Paulsen and Zimmerman-Smith created acknowledges the hesitation some may feel toward the public expression of grief but emphasizes the benefits of collective mourning.

Paulsen is now exploring what The Honor Project would look like in oncology settings where the mortality rate is lower, or in completely different health care fields, such as nursing homes or veterinary clinics.

“We struggled with the fact that The Honor Project is so simple: You write the patient’s name on a card and then later gather and connect. That’s all it is,” Paulsen says. “Part of my brain said we have nothing of value to add, but Professor Leichter reminded us that even the simplest things that should exist everywhere often don’t. That was our goal: to spread the project wherever it’s needed.”

To learn more about The Honor Project and to watch Paulsen’s video, visit The Honor Project.