Pace on Space

Policy history and promise

Over two sweltering nights in July 2019, half a million people crowded onto the National Mall to witness the transformation of the Washington Monument as an image of the Saturn V rocket that launched Apollo 11 into space was projected onto it.

The event marked the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landing and another turning point in history— the space program had captured the imagination of the American public once again.

A smaller but equally enthusiastic crowd packed an auditorium at Caltech a month later to see Scott Pace ’80, executive secretary of the National Space Council, deliver his lecture, “Apollo to Artemis: Policy History and Promise.”

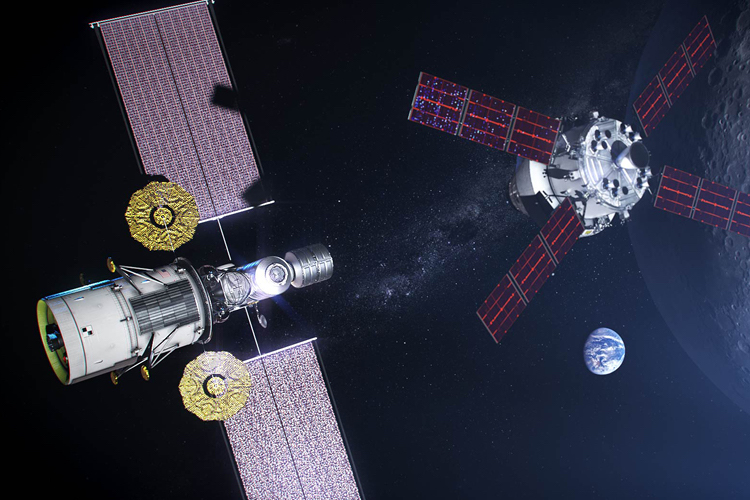

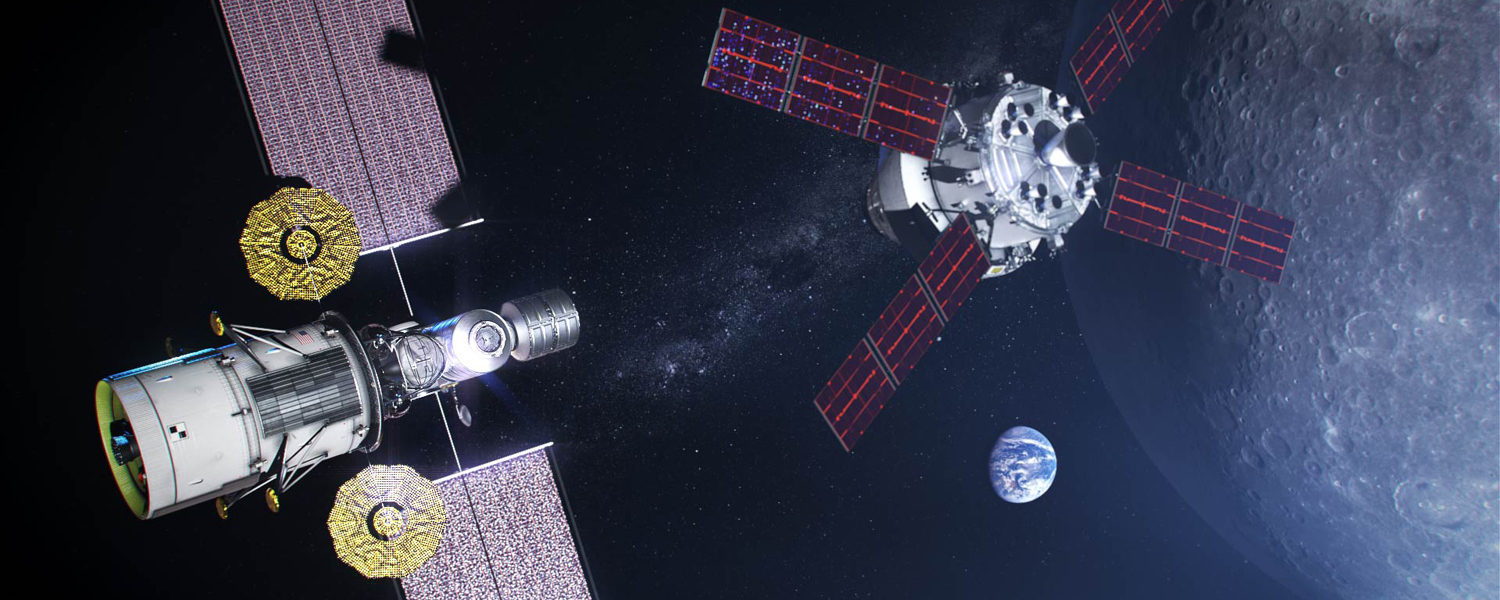

Pace contrasted the goals, challenges and debates surrounding the Apollo mission with those of the Artemis program—NASA’s next venture into space, which, in his words, “is beginning in a very different global political, economic and technical environment for human space flight.”

The origins of Apollo

The space race was initially seen as a competition between two ideologies: Soviet communism versus Western democracy.

“In 1961, you could still think that this communism thing might work out,” said Pace. When the Soviet Union launched the first man into space, it was seen as a “symbol of post-World War II Soviet economic and technical capabilities, which was very attractive to the then decolonializing third world.”

In May of 1961, President John F. Kennedy stood before a joint session of Congress and set the goal of landing a man on the moon. Why the moon? According to Pace, “Kennedy wanted dramatic results in which we could win.”

It was a political question. We could have chosen to put a lab in space or orbit the moon. We chose a lunar landing because it leveled the playing field with the Soviets.

“We could do a lot of these things, but it was not clear that the Soviets wouldn’t beat us because they already had quite a lead,” said Pace. “If we started with something as dramatically hard as a lunar landing, it was an even match.” But the success of Apollo was far from assured. It faced enormous technological, political and economic obstacles.

When Neil Armstrong stepped onto the moon, it was a singular moment in human history. As Pace sees it, that very fact may be holding us back today. “Something that was done once, you think, that’s the way other space projects have to be done. … Large national direction, big amounts of money. It all wraps up and then ends. And what comes next?”

On to Artemis

Fifty years later, the Artemis program is underway with the goals of putting another man and the first woman on the moon by 2024, and to establish a long-term presence on the lunar surface, with the horizon goal of sending humans to Mars.

According to Pace, Artemis will require both commercial and international partners, and will build on cooperation that began with the International Space Station. “We have relationships among thousands of people worldwide, including our Russian colleagues, whom we like and respect and work with very well, governments notwithstanding.

“Apollo was all about ‘look what I can do by myself,’ he said, “whereas today we have a much more globalized space environment, a much more democratized environment.”

The 2024 deadline was, Pace said, “a bit of shock to the system.” But he sees an upside. “Yes, we have technical problems. Yes, we have budget problems. The biggest problem we have is political risk as you try to do major programs across multiple administrations and multiple congresses. … If it’s really ambitious and difficult, but still possible to do, as Apollo was, then the bureaucracy goes, oh, I might actually be accountable for this.”

The big question

“The point, in my view, of exploration,” said Pace, “is to be able to answer this question: What is the future of humans in space?”

Can we live off the land, or do you have to haul everything from Earth? Can we find something economically useful to do? According to Pace, the answers to these questions are profoundly important. “Either we have a future off the planet or this is where we will always be.”