Finally, Full Mudders

Class of 1972 alumnae describe their part in making Harvey Mudd dorms co-ed

WITH THE FEMALE POPULATION AT HARVEY MUDD College now at 48 percent and with 99 percent of students living on campus, it may be difficult to imagine a time when women were few and were not allowed to reside here.

Two women who do remember such a time are Barb McNaughton ’72 (IPS/systems engineering and applied math) and Joanne Shore ’72 (physics). They were among the eight female students in their entering class who were required to live at Scripps College, the women-only college across the street from Harvey Mudd. With the knowledge that a new on-campus dorm would open at the start of their sophomore year and emboldened by protests happening around them (Vietnam War, Civil Rights), they decided it was time for a change.

McNaughton recalls she and the other first years were placed in four different Scripps dorms. Not ideal.

“In fact, we were probably in dorms that were about as far away as they could be,” she says. She and Shore became roommates during their second semester and began talking about why they should change their living situation.

“We often had projects that were designed to be group projects, and Scripps had a curfew,” recalls Shore. “Now, if you were a Scripps student, that curfew wasn’t quite as critical. But we had to be back from HMC and in our room at Scripps by 9 p.m., and that made it difficult when working on group projects. Most of us were not always able to get everything finished and wrapped up by 9 p.m. So, this was one of the aspects that was obnoxious.

“Also, there was the more general issue of not being fully integrated with the school. A lot of what goes on, goes on with dorm life and with being able to mix with your fellow classmates. So, we were feeling isolated by living at Scripps.” As Scripps residents, they also were expected to be at dorm dinners at least a few times a week.

McNaughton remembers that some of the Scripps dorms included upperclass Mudd women, but others did not, which limited interaction to their own roommate or to one’s own age group. It also wasn’t an arrangement most of the HMC women were used to since they had grown up attending co-ed schools. Most of their classmates agreed that a move to the HMC campus would be welcome and encouraged McNaughton and Shore to push for a co-ed dorm.

McNaughton began to research the issue. She discovered that the arrangement with Scripps was not binding and that it would not cost HMC money to reduce the number of its students residing there. Scripps was short on dorm space, so it had no concerns. McNaughton and Shore presented their argument to William Swartzbaugh, dean of students from 1968 to 1971, who, they say, was not at all receptive.

“At one point in his conversation,” Shore says, “he was still digging his heels in, and we said, well, we are just going to have a sit-in in front of your office until you can make your mind up.”

McNaughton adds, “I think we literally said we were going to sit in front of the administration building—you know, the overnight campout thing—until this was done. He was not too pleased with that.”

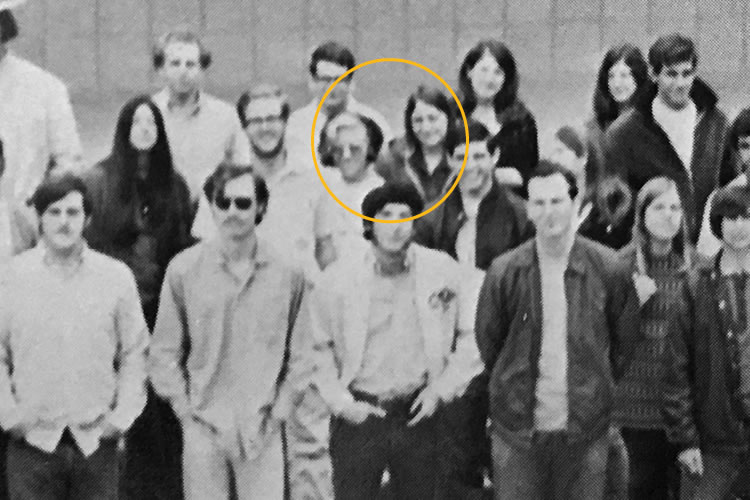

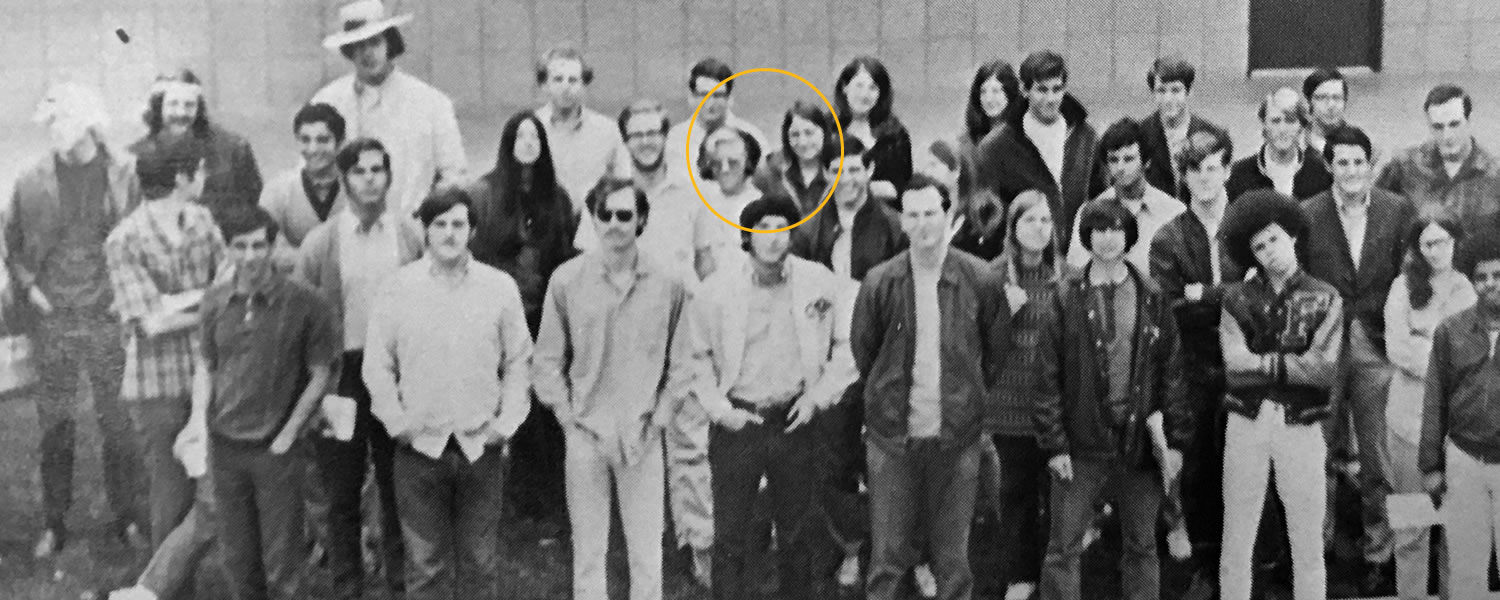

After conferring with other members of the administration, Swartzbaugh agreed to their request, and by the next year (fall 1969), the newfangled idea of a co-ed dorm became a reality in Marks Residence Hall (aka South Dorm). Ten women occupied three of the four suites in one wing, with the fourth suite being faculty office space. (“It was quite clear they didn’t want to have a boy-suite on our wing. At least they didn’t put any bars on the stairways,” says McNaughton, laughing.)

“It was a good move. No regrets,” says Shore, who has enjoyed careers in nuclear design (Bettis Atomic Power Laboratory) and in the energy field (including Gulf Oil). “I think it worked out exactly as we hoped it would. We had complete privacy and never felt like that was an issue. And we were able to interact with our classmates, get our projects done and not worry about curfews. Dorm life at Scripps didn’t include the occasional pranks, so we could finally enjoy this part of HMC life. On one occasion, our suite’s inner hall was stuffed with wadded newspapers, floor to ceiling. We reciprocated by stapling paper cups together over the entire carpeted room and filling the cups with water.”

By their senior year (1972), the dorms were available to all HMC students, though there were no intermixed bathrooms. Today, Harvey Mudd’s nine residence halls are co-ed throughout, bathrooms included.

While McNaughton and Shore appreciated their time at Scripps and the friendships made there (many of which they maintained), they have no regrets about their co-ed housing crusade. McNaughton, who spent her career working as an engineer and project manager for G.E. and IBM, believes it’s important to share their story. “Even the guys in our class didn’t realize how big a step forward this was.”

Women Hours

In Harvey Mudd College: The First Twenty Years, Founding President Joseph Platt makes reference to the housing situation for women: “’Women Hours‘ (the times when women students are permitted to visit in male dormitories) were a sore point for HMC women over the years they were housed at Scripps College. Under the Harvey Mudd College Honor Code, students are permitted to study together unless a specific assignment is to be done alone. When we had relatively few women students, and they lived in separate dormitories, the advantage of cooperative study was effectively denied many of them. Students everywhere chafed about the social regulation implied in ‘women hours;’ for our women these hours also constituted an educational disadvantage.”