Faculty

Fifty Flipping Years

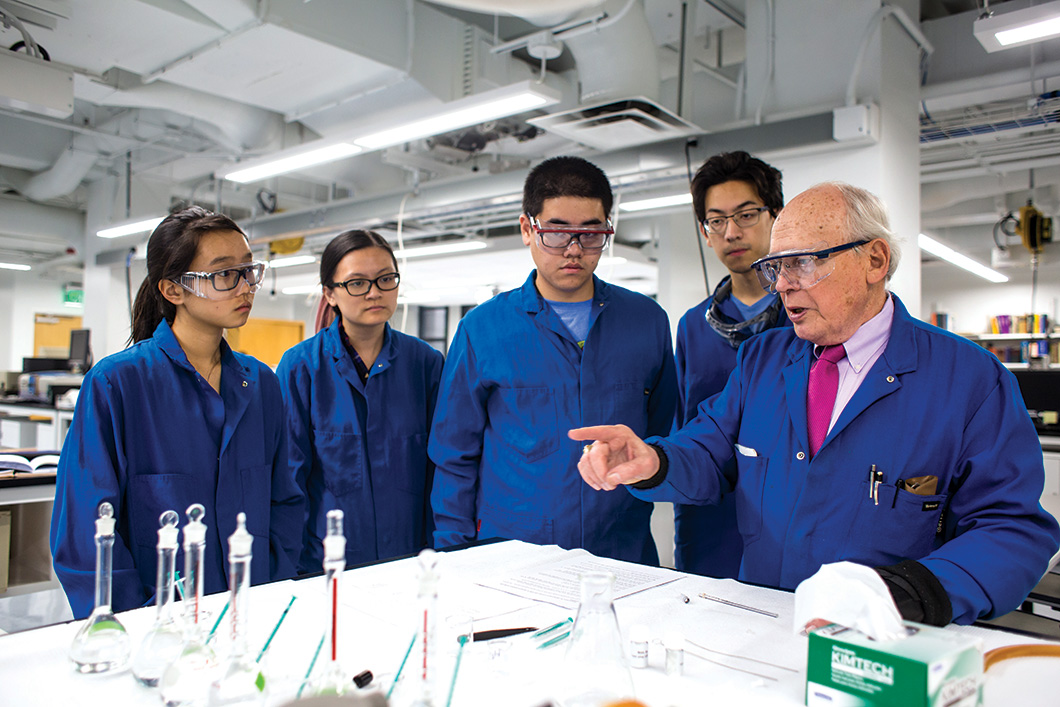

Founding Class member Gerald Van Hecke ’61 celebrates a half century of teaching at HMC.

The probability of a coin landing on its edge is rare—maybe 1 in 6,000. But that is what occurred in 1960 when Gerald Van Hecke ’61 took out a silver 50 cent piece and flipped it to determine his Harvey Mudd major.

He told his roommate Don Gross ’61, “Heads it’ll be engineering. Tails, it will be physics. And if it lands on the edge, it’ll be chemistry.” The coin bounced off his hand and straight into a crack between the sidewalk and the platform of East Dorm. So, chemistry it was.

After earning his bachelor’s in chemistry (with distinction) and a master’s and PhD in physical chemistry from Princeton University, Van Hecke worked briefly as a chemist for Shell Development, then returned to teach at HMC. Fifty years later, the Eagle Scout and former chemistry department chair is celebrating a milestone and reflecting on teaching, research, his many students and what it’s like experiencing a rarity of another kind: being a faculty member at one’s alma mater.

When I came on board, a piece of chalk and a blackboard were your means of communication. One of the biggest changes in education was the Xerox machine. Before that, we had mimeograph machines that involved a lengthy process. So if you wanted to hand out a homework assignment tomorrow, you had to plan a few days ahead. The Xerox machine brought us the ability to put an image on clear plastic sheets to use on an overhead projector. You could prepare things ahead of time by xeroxing your images and drawings onto a plastic sheet. Or you could use the plastic sheet and draw on it. So a lot of people put the chalk down and just wrote on plastic sheets. The overhead technology had a tremendous impact on people.

And then came the computer around 1984. I became a devotee of PowerPoint around 2012. I do virtually all my presentations with it. That actually made this [pandemic] shutdown pretty easy for me; with Zoom and PowerPoint, I have very little disruption from the way I present classes. The technology is really there to provide new things. I just hope that people don’t get so enamored of it that they forget that you’re talking to a human who has a finite brain, comprehension and concentration.

Mits Kubota (HMC 1959–2000), who had just started teaching when I was a junior, and then of course was on the faculty when I came back, gave me some important advice: travel. Go to meetings. And I did. When I joined the faculty at Harvey Mudd I got into an area that was just beginning and was entirely new to me: liquid crystals. I didn’t draw on PhD work or what I had done at Shell. The International Liquid Crystal meetings were held every second year and, in the off year, the American Chemical Society held meetings. I had a meeting of a professional nature involving liquid crystals somewhere in the world every year. After over 30 years of attending these, I racked up a few name tags; only a small part of them are on a wall in my office.

That’s something I pass on to junior faculty—go to meetings. It’s a way to develop and meet new colleagues and, probably even more important, to try and publish papers.

Students are the research. From the first days, there were few times I actually went in to the laboratory and did things myself. We’d find students who were interested in a particular area that I had a mutual interest in. The first couple years in liquid crystals, I’d never made one in my life. So we looked at how to make them. I’d work with a student to make sure that they put the ground glass joints together and didn’t heat something that was a closed vessel with a flame. We would get results and pursue the next steps based on those results. Students do the work, and it’s my job to help them understand what they’ve done and prepare communications telling the world what we’ve done in papers and presentations. But students have been the heart of it, and I think that’s been one of the strengths of the College.

There are fundamental things in every discipline that haven’t changed. There are a lot of things that have been added to those disciplines. Chemistry is an immense field. How do you choose a selection of topics to introduce your first-year students to the subject of chemistry? Everything in the world is a chemical. Our current chemistry program has selected things, but who’s to say they’ve selected the right thing? With knowledge multiplying maybe twofold every 10 years, that’s a factor of eight already. It’s picking and choosing, and that is a major challenge for all science. Faculty can pick their favorite topics, but a litmus test for every course should be what do our students need to know.

Among Harvey Mudd’s institutional successes is our broad education—the taking of biology, engineering, mathematics, physics, chemistry and humanities courses. The fact that we are not trying to turn out a specific type of chemist or biologist or engineer. Another success is the development of undergraduate research. That started at the College in 1958 with a chemistry colleague who came from the University of Washington with a fresh PhD and hired students into his lab and started a research program in the department. Now one of the hallmarks of this institution is the extent and the quality of the performance of our students in independent undergraduate research. And, of course, the Clinic programs. Clinic started later than research and has developed into an outstanding program.

Those three I’d say are the most outstanding attributes of the College: the broad-based education that includes the humanities, independent research and open-ended Clinic projects.

The highlights from my career so far are aspects of teaching as a deferred reward—when students come back and tell you how much they appreciated what you did. Also, students don’t pull pranks on faculty they dislike. One day I found my office full of paper cups on the floor—full of water. It turns out if you get a broad enough piece of cardboard or wood, those paper cups are strong enough together to walk on. So that’s what I did, and it was no problem.

In terms of appreciation, it was really pretty nice a couple years ago when some people put together a solicitation to build a fund in my name to support chemistry students. That’s a really nice thing to have somebody do for you.