Chau 4 Change

Educator turned administrator Derrick Chau ’97 seeks solutions with the broadest impact.

ATTRACTED BY HARVEY MUDD’S STEM FOCUS, DERRICK CHAU ’97 enrolled at the College and began studying chemistry with an eye to becoming a doctor. He’d return home during academic breaks to Fresno, California, where he worked in a hospital emergency room. After many grueling shifts, Chau came to a realization. “We were fixing people up and sending them on their way,” he recalls. “The root causes for why a lot of people ended up in the emergency room had to do with poverty, homelessness and related problems. It went beyond medicine.”

He eventually left the premed track, his sense of social justice tipping the balance in favor of a career in education, where he felt he could better address the root causes of the problems he’d seen manifested in the medical field. Inspired in part by his teachers in high school and at Harvey Mudd, Chau sought to make a positive difference in people’s lives. Right after Mudd, he taught chemistry and physical science for almost two years at David Starr Jordan High School while a member of Teach for America, a national internship program that puts aspiring teachers into schools in low-income communities. Chau was captivated by the writings of Jonathan Kozol, whose seminal book on education, Savage Inequalities, examined various school systems, revealing gross disparities in resources and outcomes between urban students and those in wealthy suburban school districts. “I had a lot of questions about why things were the way they were,” says Chau. “My mentors at Harvey Mudd and later at Loyola Marymount, where I studied for my teaching credential, encouraged me to look at education policy work.”

Chau attended the University of Southern California to earn his doctorate in education policy and then did a postdoctoral fellowship from 2002 to 2004 at the RAND Corporation, where he co-authored the “California State Charter School Evaluation,” at the request of the Legislative Analyst’s Office, the state’s nonpartisan fiscal and policy advisor. It was the early days for charter schools, the first one in California having opened in 1993, and Chau’s report found that the charters were broadly cost-efficient and viable, but that the schools needed improvement in the areas of financing and accountability.

After his time at RAND and the more abstract work he was involved with there, Chau yearned to return to the classroom. He was hired by Alliance, a charter school management nonprofit, to teach high school science. Recognizing his talent, Alliance soon tapped Chau to be the founding principal for their Marc and Eva Stern Math and Science School.

The significance of his vacillation between teaching, policy and administrative work is not lost on Chau. “My career journey has afforded me the chance to see a lot of different approaches to education, and I have learned a lot about balancing spheres of influence,” he says. “As a teacher, I felt like I was sort of in the trenches and could identify the problems readily, but I did not have a lot of control over the solutions. As a principal, all the ideas coalesced in a way that I felt like I could work the policy solutions, work the politics and implement changes in the classroom.”

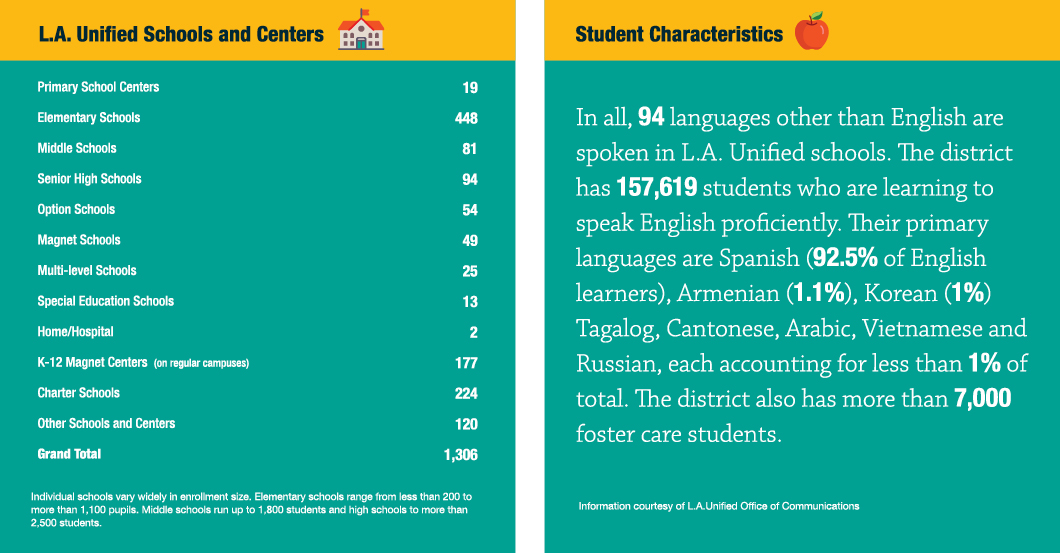

In his continuing search to have the broadest impact possible, Chau moved into teacher development, first as vice president of instruction at Alliance, and then in the Los Angeles Unified School District, where he is now the senior executive director of instruction. “It was a logical progression,” says Chau. “It has given me the chance to develop other leaders and to provide support to principals and teachers so they can be more successful in their schools.” He recently served on the 17-member Negotiated Rulemaking Committee, which was tasked by the U.S. Department of Education to help navigate the nation’s transition from No Child Left Behind to the next iteration of national education policy, the Every Student Succeeds Act.

In March, he joined Chiefs for Change, a coalition of leaders who share ideas and support each other as they seek excellence and equity for all students. Chau says this opportunity will allow him to learn from sitting superintendents as he prepares for future leadership in large urban districts. “I’m particularly attracted to the equity focus of the Chiefs for Change, the recognition that education is a primary driver for improving the pathways for students and families,” he says. “I also deeply appreciate the need to diversify the leadership pipeline in education as the demographics of our schools have changed over time.”

One of the biggest debates in education is about the role of charter schools within public school systems. “If there were a silver bullet, someone would have packaged it and made a lot of money by now,” says Chau. The friction over charter schools usually is not related to student issues, he asserts. “Control over the schools and budgets are an adult problem. So often in the past, school districts have required students to attend public schools that have been underperforming.” Charter schools offer another option for those students and their parents. Chau points out that low-income families can’t just pick up and move to another district or send their child to a private school. In their favor, charter schools are primarily nonprofit, and they serve as laboratories for new ideas in education.

On the other hand, Chau maintains that with the greater autonomy granted to the charter schools, they must be subject to greater accountability as well. “What is needed is the ability to view all sides of the issue,” Chau says. “Right now, there is a lot of partisanship without a lot of understanding, and that’s not helping.”

Having seen the debate from many sides—as teacher and administrator, researcher and practitioner, and within both public and charter schools—Chau is using his role at LAUSD to help all involved get to the root of issues.

“I feel fortunate to be an educator at this level who’s been able to have all the experiences I’ve had,” says Chau. “It won’t be easy, but we’ve got to find the best solution for our students.”